-

Save

The top-floor attic of Jerry and Dorothy Lemelson’s New Jersey home was an idea factory, library and legal shop rolled into one.

It bulged with notebooks and legal pads filled with invention ideas, detailed drawings of toys, consumer and medical products, and complex systems. There were dozens of half-finished patent applications; magazines from the worlds of science, engineering, medicine and many other fields; and scores of legal briefs that no one in the Lemelson family but their author could begin to fathom.

The Lemelson boys, however, were not deterred by the evidence of their father’s ever-active mind that lived on shelves, on their father’s desk, and in boxes and closets on the attic floor.

They snuck up to the attic when their father was not home and explored.

Jerry Lemelson’s lair was more than a place for him to create, and for his sons Eric and Rob to investigate. If some voice from on high were to order a mere mortal to locate the geographical origins of The Lemelson Foundation, Jerry Lemelson’s legacy project, it would point to that sprawling attic room.

A genius’s lonely world

The life of an independent inventor is challenging and often lonely. Driven by some indescribable internal drive to create, one may toil for decades, often with little external validation.

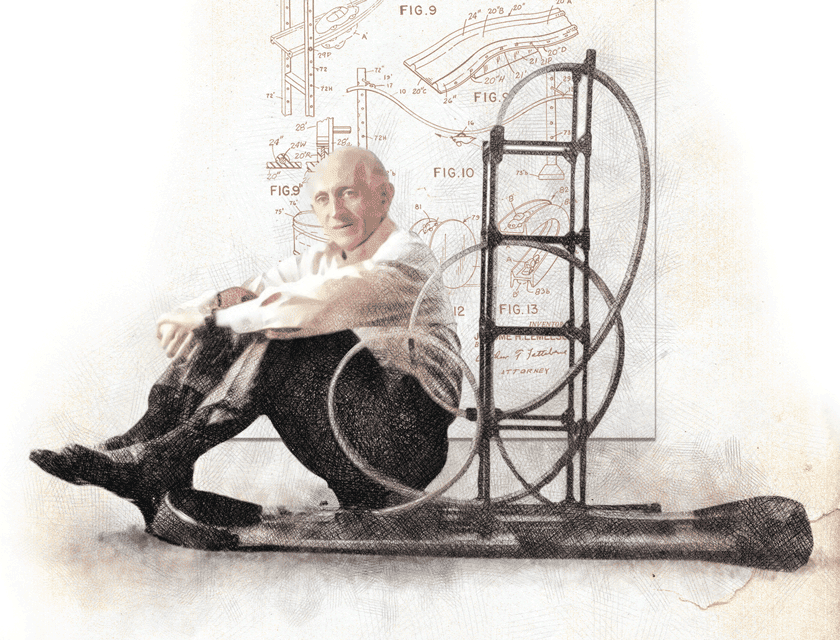

Jerry Lemelson was in many ways no exception to this rule, at least until late in his life. His 600-plus patents spanned fields ranging from toys and other consumer products to medical devices, to information processing and automated manufacturing systems that in many cases were decades ahead of their time. Yet he was relatively little known outside of the U.S. Patent Office and certain inventor circles until the early 1990s, a few years before his death.

On the day he died, however, his patent portfolio ranked among the largest granted to any inventor in U.S. history.

Unlike other inventors such as Thomas Edison, who employed teams of engineers, designers and subject-matter experts, nearly all his inventions were the sole work product of one man. No one who knew him well would disagree that Jerry Lemelson lived to invent and create, a solo artist whose canvas was the world.

Ultimately, Lemelson’s inventing acumen produced an automated warehouse system; an automated machine shop; a cassette drive mechanism that appeared in every Walkman; a talking thermometer for blind people; some of the basic components of the desktop computer, licensed to IBM; and much more.

He told an attorney friend that his most important invention was “machine vision,” in the mid-1950s—a system in which a combination of computers, robotics and electro-optics allows assembly-line robots to assess an item and determine what work needs to be done to it before adjusting themselves to perform multiple operations on the item, and even perform quality control of the work when it’s done.

While he spent decades focused on the details of his inventions and of the court battles he engaged in to protect his intellectual property, Lemelson also saw the big picture. He grew up during an era of U.S. economic dominance—a product of the outcome of World War II—and of significant U.S. government investments in science and technology to win the war, as well as in education; basic research that undergirds groundbreaking innovation; and a political climate that fostered broad prosperity and the cementing of a strong middle class.

Lemelson understood, from his education and life experiences, that long-term U.S. economic success in a rapidly changing global economy was never guaranteed—that, in fact, it could be fleeting if the country failed to understand, recognize and cultivate the reasons for its success.

Protect the patent system, support the development of the next generation of inventors and innovators, know what sets the country apart from its competitors, he thought, and we can remain a free, prosperous and stable nation for generations.

Throughout his career, Jerry Lemelson fought doggedly for his rights and those of other independent inventors. He served on a federal advisory committee on patent issues from 1976 to 1979, and continued to look for opportunities to advance the cause of inventors throughout his life.

Inventing to the end

Eric Lemelson, now a co-president and treasurer for the foundation, shared a story that illustrates his father’s lifelong drive to invent.

His father was diagnosed with stomach cancer the year before his death in 1997. While he was being treated, “he had multiple endoscopies where the examining physician sticks a device called an endoscope down your throat to inspect the stomach. To me, it sounds pretty unpleasant!

“But he was fully present during the exam, paying careful attention to what the doctor was doing. After the scope was withdrawn, he continued processing his observations and thoughts—and within weeks or months, he filed a patent on an improvement to the endoscope.”

Lemelson was granted more than 20 medical patents posthumously, based on work he did during his unsuccessful chemotherapy treatment. He worked “right up until two weeks before his death, when he could no longer sit up in bed,” Eric said.

“Jerry’s creative drive was all-consuming, because even at a moment when most folks would understandably choose to distract themselves, he was focused on problem solving.

“Problem solving was essential to his being.”

The light was always on

Rob Lemelson, co-president and director of the foundation, has committed considerable time and energy to understanding and exploring the reasons for his father’s inventive fire.

In his private and poignant documentary about their father, “Patent Man,” he interviewed Jerry’s middle brother, Howard, a New York-based engineer and entrepreneur. Howard described how they shared a small apartment in Manhattan when they were in graduate school.

“There were two beds and one night table. And on the night table, there was a lamp, a legal book, and a pen.

“Almost on the hour, Jerry would wake up, the light would go on, he would enter a new idea in the book, the light would go off, he’d go to sleep—and the next hour, the same thing.

“In the morning, I had six to eight inventions to witness, and I did (via his signature and date). This happened every night, seven nights a week, every week.

“Jerry had the most fertile mind of any man I ever knew. He could look at you, and he could see something that he’d like to invent that would make you better than you are.”

Rob Lemelson explained how his father imagined things others never thought possible.

“Eric and I would always give him a hard time. I remember he told us in the early 1970s that ‘I have this idea that satellites will gather data and send a signal so that you can navigate on the ground using a satellite miles overhead in space.’ … We said, ‘Why would you work on something that we will never see in our lifetime?’

“Jerry had this ability to look out 30 to 40 years, and understand in detail what the world of technology would look like. It was remarkable.”

Persistence and heartbreak

Though gifted with a keen vision to “see” and understand the march of technological development in his imagination and mind’s eye, Lemelson was arguably born at the wrong time.

“My father grew up during the rise of corporate consolidation of the innovation process–when large corporations began to play a dominant role in inventing and patenting products and technology,” Rob Lemelson said.

”Corporations had what Jerry called the ‘Not-Invented-Here Syndrome.’ He observed that they were rarely open to inventions and product ideas from outside their own organizations, even if they were directly relevant to their existing or planned product lines and could transform the bottom line.”

Corporate titans like Henry Ford were infamous for ordering their attorneys to squash independent inventors and their intellectual property claims like bugs. That attitude persisted (perhaps to this day) and affected independent inventors like Lemelson.

As someone whose greatest gifts were in envisioning, designing and perfecting inventions, rather than in business formation and development, Lemelson struggled financially throughout much of his early and mid-career.

Though his early inventions included forays into complex technologies like automated manufacturing systems, he put considerable energy into inventing toys and games. He believed that toys were easier subjects to interest companies in licensing.

Ultimately, he spent more than 30 years in licensing efforts, which often frustrated him. In his view, corporations stole many of his ideas. Even today, his sons remember visits to toy stores with their father as he took pains to point out his creations on store shelves.

However, when he sued to defend his patent rights, he found that the legal system was extremely difficult for independent inventors to navigate successfully.

In his view (and in the view of numerous other independent inventors), judges rarely had exposure to engineering, design and technology development, and the patent system represented a rather obscure corner of the legal world. Inventors like Lemelson experienced the hostility that many courtrooms exhibited toward inventors who fought to defend their intellectual property against corporate behemoths. Many, if not most, patent lawsuits by inventors were dismissed or thrown out of court during much of Lemelson’s long career.

Lemelson’s efforts to defend his work met with some success, But he often left court empty-handed.

His most devastating defeat came in 1992, when the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit overturned a 1989 ruling by a federal district court in Illinois that Mattel Inc. had infringed on his patented orange flexible track used for the Hot Wheels mini toy car line.

The jury had awarded Lemelson $72 million. Now, after years of courtroom struggles and millions of dollars in legal bills, he was left with nothing but heartache.

Jerry Lemelson wept about what was lost, but it wasn’t the money.

“The facts of what happened in the Hot Wheels case were very clear to my father; he saw the outcome as fundamentally unjust. It was probably the worst defeat of his life,” Rob Lemelson said.

A foundation born

Within a few years of his defeat in the Hot Wheels case, Lemelson’s fortune began to turn in a major way.

In the early 1990s, he licensed a series of patents to numerous companies in Asia, and later the United States, but not before a series of major court battles.

Rob Lemelson remembered his father’s determined pursuit of his goals.

“Jerry was a total fighter. He took on the largest corporations that had armies of attorneys and pretty brutal tactics. There was quite a concerted media campaign against my dad during that period, and so he was pretty upset.”

In 1991, the brothers went for a walk in Los Angeles’ Will Rogers State Park with their father.

“We sat on the grass and talked with Jerry about the arc of his career,” Rob said. “I think we were trying to turn his attention away from the campaign against him by his opponents and the critical media that was the product of that effort. We explained that, after all these years of struggle, he now had the resources, the freedom of action and a vision to work towards.

“We reminded him how often he talked about how important inventors and innovators were to America’s place in the world, its strong middle class, its global leadership. We discussed his passionate belief that we needed to cultivate the next generation of American inventors among young people.

“Jerry would say: ‘We make sports players into national heroes. Why not show young people that inventors can be heroes, too?’ We closed with a simple proposition—that he finally had a clear path to realize his vision, so why not do something with that? And he immediately jumped on it.”

Within less than a year of that walk, Jerry Lemelson and his family had formed The Lemelson Foundation. Their founding mission: to improve lives through invention.

Initially, Jerry Lemelson chose as Lemelson Foundation partners several highly respected educational and cultural institutions. His overriding goal was to raise the profile of invention and innovation in America.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology was one of the organization’s first partners, with the Lemelson-MIT Program the first such effort. It began with the world’s largest cash prize for an inventor, first awarded in 1995 and continuing until 2019, as well as a national Student Prize awarded to a top student inventor at the graduate school level.

Today, the program has transitioned to focus on invention education, based on the proposition that the ability to invent and innovate is innate to our species and can be cultivated, supported and taught.

The foundation also partnered with the Smithsonian Institution in its first few years of operation to establish and later endow the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation at the National Museum of American History. The extensive, interactive exhibits in the center inform and inspire young people and other museum visitors about the importance of innovation. The center also conducts research into the role of invention and inventors in the American economy, culture and history.

At the official dedication of the Lemelson Center in 1995, Jerry Lemelson said: “The spirit of invention is a basic ingredient in our democracy.

“In 1776, this nation invented itself. We discarded all the old models in favor of a dazzling experiment that forever changed what people mean when they say the word ‘freedom.’

“So creative and far-sighted were the founders of this nation that our Constitution makes direct reference to stimulating invention and innovation.”

Innovation in education

In 1995, Lemelson and his sons sought to create a new organization to explore the team-based approach to student inventing and enterprise development.

They were introduced to Phil Weilerstein, a young engineer at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. Out of that meeting grew the National Collegiate Inventors and Innovators Alliance, which later became an independent nonprofit called VentureWell.

The organization’s founding thesis is deceptively simple: support college students who form teams to produce product ideas that eventually become businesses and grow the economy. As these teams develop, students learn critical skillsets that 30 years ago were not taught in schools—including patenting, business development and marketing—and later, working with angel investors to get their ventures to scale and impact.

Weilerstein is still leading VentureWell, now a multi-million-dollar nongovernmental organization with hundreds of schools involved in its consortium, and hundreds of successful businesses that prove the real-world applicability that originated with Jerry Lemelson’s ideas. Although Lemelson was a quintessential independent inventor, he understood that collaboration often plays an essential role in innovation.

His sons ultimately acquired their father’s visionary bent with their own ambitious, big-picture pursuits.

Rob, a PhD, psychological anthropologist and documentary filmmaker, started The Foundation for Psychocultural Research in December 1999 to support and advance interdisciplinary research bridging anthropology, psychology, psychiatry and the neurosciences, and is a noted documentary filmmaker.

Eric, an environmental lawyer, started the Karuna Foundation in 2010 to contribute to the pressing issues of climate change mitigation and adaptation in the vulnerable Himalayan region. He is also a winegrower and winemaker in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, and designs and develops energy-efficient buildings in the United States and abroad.

Essential support

Dorothy Lemelson played a central role in her husband’s career. “Jerry could not have succeeded without my mom,” Eric Lemelson said.

Dorothy’s income as a businesswoman allowed Lemelson to invent and create without having a regular income; her advice, perspective and faith in him were indispensable elements in his eventual success.

“Dolly” Lemelson was a gifted visionary in her own fields—design and aesthetics. Graduating from Parsons School of Design in Manhattan in 1947, she started an eponymous interior design firm.

In a short film Rob made about her life, she said with a laugh about her husband: “He was different from most people. … Someone did say to me that if I stopped working, Jerry might get a job. So you can thank me for the fact that I continued to work.”

After Jerry died, Dolly became president and chair of The Lemelson Foundation’s Board of Directors. During her tenure as president, she and her sons broadened the focus of the foundation, expanding its impact regionally, nationally and globally. K-12 invention education became an important part of the foundation’s grantmaking under her leadership. She died in 2021.

“She complemented Jerry very well,” Eric said. “Jerry had his immense gifts and his creativity and his vision. Like many gifted scientists and engineers, however, he wasn’t always good at reading others, and without my mom’s advice, he might never have reached his full potential as an inventor.

“She worked as his partner without appearing on his business cards, but in terms of his interactions with others, her gifts shaped outcomes and influenced his perspective in the most important ways.”

Future vision

The family believes that The Lemelson Foundation has progressed and grown in ways that Jerry would understand and appreciate.

Today, in addition to its legacy programs, The Lemelson Foundation has a strong focus on global impact through its programs in the developing world. In the early 2000s, the family chose to refocus a significant portion of the foundation’s programming on inventing for sustainable development in the rapidly growing developing world.

The family’s experiences, beliefs and values, including spending time in the developing world; a strong commitment to equity and social justice; a respect for people from all backgrounds, and an awareness of the increasing interconnectedness of the human family all drove the program’s development.

Its initial programs funded grassroots inventor support in countries that included India, Kenya and Peru. Today, its International Entrepreneurship strategy supports the development of broader invention ecosystems. That strategy currently focuses on India and Kenya, supporting an approach to cultivate inventors who address social, economic and environmental challenges.

In 2023, the foundation announced a seven-year, $50 million Climate Action initiative to support innovative approaches for dealing with the climate crisis by decarbonizing the global economy.

Eric Lemelson said: “If my father was alive today, he would understand on a deep level the need for invention-based technologies to solve what is arguably the biggest global challenge our species has ever faced.”

Aiming higher and farther

“It’s been an evolution,” said Rob Schneider, executive director of The Lemelson Foundation. “Thirty years ago, few people were really focused on the importance of invention.

“When the foundation started, I think there was a lot of attention to highlighting inventor stories. While stories are important, later we began to ask, ‘OK, you’ve got a workable invention, now how do you take it to scale, to maximize its impact?’

“We need to be inventing for all sorts of problems. You maximize impact by changing the lives of hundreds of thousands and millions of people.”

As these success stories develop, the foundation becomes emboldened to not only change outcomes but how we think about and prioritize inventing at a grassroots level.

“How do we change whole systems? I think we broadened our focus to think about what everybody can be—and that everybody should have equal opportunity to become inventive,” Schneider said.

Jerry Lemelson always challenged himself and others to expand our vision—what we can see now that can design a better future and solve important problems. Dorothy Lemelson summed up this perspective well in remarks to an audience of young people:

“I hope that each one of you is able to do something in your own life that will project something to somebody else, that is beyond what they can see.”

See more at www.lemelson.org.